Saving always Rome no Western city has ever been so much at the headwaters of an empire as London, especially at the turn of the 20th century when Margaret Edythe Young and her family visited. Ironically the city may date its modern foundation from the Romans as Londinium in 43 AD which, in spite of having been burnt to the ground by Queen Boadicea in 61 AD, became the capital of the Roman province of Britannia around 100 AD and a major city by the 2nd century AD with a population in excess of 60,000. The London of 1900 had an enormous population, reported to be nearly 6.5 million, and had considerable infrastructure and technology – electric light and gas heating, an extensive telephone network (with transatlantic line to America), an extensive underground railway network, public transport via omnibuses, the beginning of the urban love affair with automobiles – mainly taxis, a national postal service with multiple daily deliveries and the world’s largest metropolitan police force.

Joseph Chamberlain may have observed that, London is the clearing-house of the world, but Macaulay’s warning that [Rome]may still exist in undiminished vigour when some traveller from New Zealand shall, in the midst of a vast solitude, take his stand on a broken arch of London Bridge to sketch the ruins of St. Paul’s, remains the more cogent and prescient observation. In 1900 Victoria still rules, Joseph Chamberlin – the ultimate English anomaly of his day, a self-made millionaire who attended neither Oxford nor Cambridge – still served as leader of the opposition, then as Secretary of State for the Colonies and finally as President of the Board of Trade, so the forgotten warning of an academic dead some forty years was ignored. For the purposes of this entry we shall ignore it as well, happy to and simply leave it as a memento mori to all of the self-made men who continue to remake London.

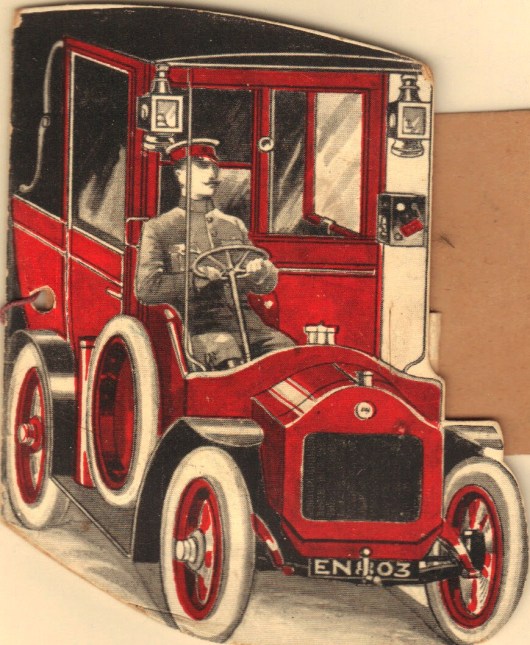

Not unlike the Views of Glasgow from the International Exhibition of 1901 we have a souvenir of London from the Photochrome Co., Ltd. London [and Detroit, U.S.A.] which is a series of photographs of the principal attractions of London. These were cleverly packaged inside a paper replica of a London taxi which had an address label attached as a tag that required a halfpenny stamp for mailing. Using the pictures of the sights they saw and contemporary sources we will try to give the reader a tour of London in 1900 AD which we hope you enjoy.

Hyde Park with Kensington Gardens, which is a continuation, covers over 630 acres. The popular entrance to the park is at Hyde Park Corner, at the end of Piccadilly where in the season the long drive is crowded in the afternoons with citizen and gawker alike walking it length to the Marble Arch, close to Edgware Road at the end of Oxford Street. The flower gardens in the spaces opposite Park Lane, and the Rotten Row [a bridle path reserved for the saddle horses of the quality] was supplemented with a fine display of Rhododendrons in the early summer.

The Achilles Monument, inside the park from Hyde Park Corner, had been placed in memory of “the great Duke and his companions in arms” near Apsley House, the residence of the Duke of Wellington, that was close to that entrance. Considering that in the 20th century it would become the site of every lunatic with a soapbox ranting about ideas and goals that Wellington would have had them whipped for proves that history may have a sense of humor.

The Serpentine runs almost across the park on which boating and bathing were permitted. Based on a letter to the Times – from 1848 – these waters must have been substantially cleaned in the intervening half century if they were used for recreation at all; At the present time the Serpentine is truly a water-hole – a stagnant pond – the recipient of delinquent or unfortunate dogs and cats – the outlet for much other indescribable filth, and the reservoir of sickening and putrefying fish. Several eminent physicians most distinctly pointed out the many evils resulting from it. The Free Watermen complain that no one will ride in their boats on account of the filthy water; the medical profession advise their patients not to lounge near this cloaca maxima; and the bathers are fairly frightened away. As one of the many who bathed hitherto in Hyde-park, but now one of the multitude who dread such a method of lubricating our skins, I beseech you, Sir, pray take us under your protection; for if you will but take up the cudgels, the matter will be settled.

What is now the Chelsea and Westminster Hospital at the old St Stephen’s Hospital site in Fulham Road started as simply the Westminster Hospital established in 1719 as a charitable society “for relieving the sick and needy at the Public Infirmary in Westminster”. Originally located on Petty France – a considerable street between Tathill Street, E., and James Street, W – the institution moved to Chapel Street, and then to James Street before the hospital pictured here was situated by the Broad Sanctuary and the northern side of the nave of Westminster Abbey. With a capacity of 200 patients the records indicate it treated nearly 20,000 patients annually by 1900.

The founding document is worthy of consideration; Whereas a charitable proposal was published in December last (1719), for relieving the sick and needy, by providing them with lodging, with proper food and physick, and nurses to attend them during their sickness, and by procuring them the advice and assistance of physicians or surgeons, as their necessities should require; and by the blessing of God upon this undertaking, such sums of money have been advanced and subscribed by several of the nobility and gentry of both sexes and by some of the clergy, as have enabled the managers of this charity to carry on in some measure what was then proposed: — for the satisfaction of the subscribers and benefactors, and for animating others to promote and encourage this pious and Christian work, this is to acquaint them, that in pursuance of the foresaid charitable proposal, there is an infirmary set up in Westminster, where the poor sick who are admitted into it and daily visited by some one or other of the clergy.

Where the original hospital was operating within a year of its proposal the modern incarnation – Chelsea and Westminster Hospital – was designed by the architects Sheppard Robson and was built with fast track techniques in 5 years. Who says socialized medicine doesn’t work?

Great cities are not static. Their population increases, the old gives way to the new – today’s synagogue is tomorrow’s mosque – and the most fortunate manage to preserve their heritage while they grow. London was no exception and Holborn Street was a great example. Two descriptions from the same source tell its story; Holborn is a continuation of Oxford-street, the link between east and west. It is a great thoroughfare, but its shops are not of such a class as would be expected from that circumstance. Holborn, in fact, suffers from being neither one thing nor the other. It is too far east for the fashionable world to come to it for their purchases; it is too far west for the business men of the City; consequently it contains few first-class shops or warehouses… from Dickens’s Dictionary of London, 1879

HOLBORN, which is divided into Holborn proper (which reaches as far as the city boundary at Holborn Bars) and High Holborn, which extends to New Oxford Street, then turns partly to the left, is part of the upper main route from the Bank to the west and is an important thoroughfare between the two. It has within the last twenty years or so been largely rebuilt, having the huge premises in red brick of the Prudential Assurance Co., a fine building, and the high terra-cotta buildings of the Birkbeck Bank. Its businesses – Wallis’ (drapers), Gamage’s (cycles, etc.) and Baker’s (clothiers) – are well-known, and it is a good middle-class centre for shopping. The old houses opposite Gray’s Inn road (Staple Inn) are by far the most perfect specimens of old street architecture, with their wooden beams and projecting upper stories, remaining in London. On the north side are Gray’s Inn and Gray’s Inn road (leading to King’s Crossing) and on the south side are Chancery lane (leading to Fleet street) and Lincoln’s Inn. (See Inns of Court). The Holborn Restaurant is at the corner of Kingsway (the new route to the Strand) and opposite here is Southampton row, which, leading to Russell square, has become a great centre for hotels and boarding-houses of different styles (temperance as well as others) suitable to middle-class visitors… Dickens Dictionary of London, c.1908 edition

A combination of the old and the new may be seen in the Charing Cross Hotel, situated at the South Eastern Railway Company’s western terminus. Entrance to the station is from the large yard, which presented a very busy scene, especially when the Continental mail was about to start.

The hotel was built by Sir C. Barry, on the site of Hungerford Market. Charing Cross was once marked by a Monument, known as Eleanor’s Cross, which was one of a series erected by Edward I to distinguish the progress of his wife’s [Eleanor of Castile] body while en route being taken from Lincoln to Westminster Abbey for entombment.

The original was erected in 1291 but in 1647 was removed by order of Parliament. The present cross is the work of the hotel architect E. M. Barry and stands 70 feet tall in all of its elaborate Gothic glory executed in sandstone and granite. The hotel still stands and the Monument still stands and while we doubt the Monument fulfills its original purpose to provoke prayers for her soul from passers-by and pilgrims it is the sort of reminder that Macaulay would have approved of and that is needed now more than ever if London is not to become Londonistan.

On the left side of this picture is the facade of the Mansion House which is the official residence of the Lord Mayor of London designed and built by George Dance the Elder and renovated by George Dance the Younger – the two of whom held a virtual monopoly on surveying and architecture for a large part of the 18th century. Originally built between 1739 and 1752, in the then fashionable Palladian style, it offers an uneasily constricted bulk, that led Sir John Summerson to observe that on the whole, the building is a striking reminder that good taste was not a universal attribute in the eighteenth century. The entrance facade has a portico with six Corinthian columns, supporting a pediment with a tympanum sculpture by Sir Robert Taylor, in the centre of which is a symbolic figure of the City of London trampling on her enemies. While it now houses a collection of Dutch and Flemish Seventeenth Century Paintings in 1900, in his role as chief magistrate of the city, the mayor may have housed the suffragette women’s rights campaigner Emmeline Pankhurst in one of the prison cells in its basement.

One the right hand side of the photograph is the Bank of England. From Reynolds’ Shilling Coloured Map of London, 1895 we glean the following brief description of the BANK OF ENGLAND, THREADNEEDLE STREET … This world-renowned establishment was founded in 1691. The present buildings were erected mostly from the designs of Sir John Soane, 1795-1829. The principal offices are open daily, from nine to three. The bank-note machinery, bullion vaults, &c., can be seen only be special permission.

While from The Queen’s London : a Pictorial and Descriptive Record of the Streets, Buildings, Parks and Scenery of the Great Metropolis, 1896 we learn further – the chief institution of the kind in the world – is appropriately located in the very heart of the City. Its main entrance is in Threadneedle Street, and the buildings, which are, of course, isolated, cover about four acres. The Bank is mainly a one-storey structure and for the sake of security, there are no windows in the outside walls. The institution employs some nine hundred persons and more than two millions sterling are daily negotiated here, and every day fifteen thousand new bank-notes are printed, while some twenty million pounds of cash lies in the vaults below.

Rome is the city of the seven hills while London only has three one of which is Ludgate Hill and it is the highest point in the city. It had been the sight of the Cathedral since the 7th century AD. From its founding in 604 at the instigation of Gregory the Great the site housed the episcopal see. It was the Cathedral begun in about 1087 AD by Bishop Maurice, Chaplain to William the Conqueror, which would provide the longest standing home for Christian worship on the site to date, surviving for almost six hundred years. The reign of King Henry VIII saw the beginning of the end for the religious life and the buildings associated with Roman Catholicism. The shrine of St Erkenwald was plundered and waves of iconoclasm followed in which shrines and images were destroyed. The full suppression of Catholic worship and fittings was carried out under Edward VI by the first protestant bishop of London, Nicholas Ridley.

The physical destruction wrought during the usurpation had only been the start of a series of threats to the fabric. In June 1561 lightning struck the Cathedral spire igniting a fire which destroyed the steeple and roofs, the heat and falling timbers causing such damage to the Cathedral structure that it would never fully recover. Plans were made for restoration and the architect Inigo Jones (1573–1652) was engaged to carry out work in 1633, but his work was left incomplete at the outbreak of the English Civil War in 1642. Parliamentary forces took control of the Cathedral and its Dean and Chapter dissolved; the Lady Chapel became a large preaching auditorium, while the vast nave was used as a cavalry barracks with, at one point, 800 horses stabled inside.

By the 1650s the building was in a serious state of disrepair and it was only after the restoration in 1660 of King Charles II (1630–1685) that repair was once again considered in earnest. Leading architects wrestled with the how to restore the medieval structure and were often in disagreement. Inspired by his travels in France and his knowledge of Italian architecture, Christopher Wren (1632–1732) proposed the addition of a dome to the building, a plan agreed upon in August 1666. Only a week later The Great Fire of London was kindled in Pudding Lane, reaching St Paul’s in two days. The wooden scaffolding contributed to the spread of the flames around the Cathedral and the high vaults fell, smashing into the crypt, where flames, fueled by thousands of books stored there in vaults put the structure beyond hope of rescue.

Although there would be a new St. Paul’s – designed in its entirety by Wren – just over a thousand years after its founding the last remnant of the Roman Cathedral was reduced to ashes and dispersed to the winds. It would not be until 1884 that a new site was acquired by the Catholic Church in Bulinga Fen that formed part of the marsh around Westminster. The foundation stone was laid in 1895 and the fabric of the building was completed eight years later. After centuries of persecution how apt it was that the new cathedral replaced Tothill Fields Prison and that the Clergy House and the Choir School now stand on the site of the old wings where women and children were incarcerated.

In 1850 the Diocese of Westminster was created, at the Restoration of the Catholic Hierarchy by Pope Pius IX, with Nicholas Wiseman as first Archbishop. In 1903 first regular celebration of daily Mass and the Divine Office took place in the Cathedral and Edward Elgar conducted first London performance of John Henry Newman’s ‘The Dream of Gerontius‘ there. In 1906 was the unveiling and blessing of baldacchino [the canopy over the altar] and in 1910 the Consecration of the Cathedral was celebrated. 244 years without a Cathedral and a move from the highest spot in the city to a mire that had housed an infamous prison. I guess it really is the faith that matters.

Galveston did not have its seawall yet but in a few years when it did the Boulevard along the Seawall would owe as much to the Thames Embankment as the Strand would to its commercial counterparts in London. Although they are certainly not carbon copies they are built in the same spirit and like most great thoroughfares often highlight the best the city has to offer while bypassing some of the more questionable attractions.

Technically, according to The Queen’s London : a Pictorial and Descriptive Record of the Streets, Buildings, Parks and Scenery of the Great Metropolis, 1896, this was the Victoria Embankment which quite surpasses anything that is seen beside the Seine or the Tiber. Its magnificent sweep from the Houses of Parliament to St. Paul’s is one of the finest sights in the whole of London, and cannot fail to impress every observer. Cityward the most noticeable building is Somerset House, with its fine façade of 780 feet, and beyond this lie the Offices of the London School Board, the Temple Library, Sion College Library, and the City of London School, &c. The Embankment itself, the greatest achievement of the late Metropolitan Board of Works, cost nearly two millions, and its construction occupied six years – 1864-70.

Although it was a grand boulevard the careful observer will note, based on Cruchley’s London in 1865 : A Handbook for Strangers, 1865, that however magnificent on the surface it was a disguise for the fact that the Thames was essentially the sewer system for London. In connection with the Main Drainage Low-level Sewer, a scheme for an embankment of the river Thames was proposed. It is proposed to fill in an unsightly gap in the shore at Millbank, and the embankment at present projected will extend from Westminster to Blackfriars Bridges. This includes the construction of a new steam-boat pier at Westminster, and the roadway, which is to be 100 feet wide, at a height of 4 feet above high-water mark, from Westminster to the Temple, and 70 feet in width from the Temple to Blackfriars, will cross the first brick pier of the Charing Cross Railway Bridge, and the first pier of the Waterloo Bridge. A viaduct of open arches is to be constructed, to admit barges to the City Gas Works and the wharves at Whitefriars, and the approaches from the east side of Bridge-street, from “Whitehall,” and from Charing Cross, will be laid out as gardens or on building leases.

Contemporary Londoner, David Quarmy, pretty well summed up its importance, Trafalgar was a defining moment in Britain’s history as it established Britain’s maritime ascendancy for 100 years which saw a fantastic growth of trade and empire during Victorian times, and the square – with its monument to Nelson was the epitome of imperial hubris. Nelson was the perfect hero for Britain and certainly his instructions, Firstly you must always implicitly obey orders, without attempting to form any opinion of your own regarding their propriety. Secondly, you must consider every man your enemy who speaks ill of your king; and thirdly you must hate a Frenchman as you hate the devil, could have been the complete codex Victoriana.

While compared to ancient Rome, where the monuments are detailed by Augustus Hare quoting A monumental record of A.D. 540, published by Cardinal Mai, mentions 324 streets, 2 capitols—the Tarpeian and that on the Quirinal, 80 gilt statues of the gods (only the Hercules remains), 66 ivory statues of the gods, 46,608 houses, 17,097 palaces, 13,052 fountains, 3785 statues of emperors and generals in bronze, 22 great equestrian statues of bronze (only Marcus Aurelius remains), 2 colossi (Marcus Aurelius and Trajan), 9026 baths, 31 theatres, and 8 amphitheatres!, London may not have quite caught up it was in the process of mounting a competition and occasionally the humor of having a monument to George Washington facing Nelson’s column must have struck someone as funny but we have not found any quips about it.

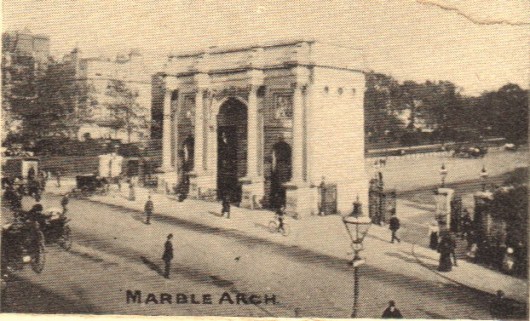

From the corners of the empire monuments by the dozens were crated up and shipped back to England just as the Romans had done. Every once in a while something caught the fancy of his – or her – majesty but was either too large or too well guarded to be conveniently moved. Given that this was the age of industry the simple thing was to duplicate it. This was the case with the Marble arch – designed in 1827 by John Nash as the triumphal gateway to Buckingham Palace.

Nash modeled Marble Arch on Rome’s famous Arch of Constantine, built in the fourth century. Both structures feature Corinthian columns and three arches: one large central arch and another on either side. In 1851 the arch was moved to its current site at Cumberland Gate, where Oxford Street and Edgware Road meet at the north-east corner of Hyde Park, after the palace was expanded and Victoria requested more personal space for her family. The arch was decorated with a number of sculptures, none of which remain with the arch and the most notable of which was that of King George IV – who had the arch erected – which sat on top of the central arch and can now be found in Trafalgar Square.

The theft of antiquities, either literally or by duplication, and the habit of self-glorification out of the public purse notwithstanding it may be said in behalf of the Victorians that they were not a wasteful lot. Not only was the Marble Arch moved but the Crystal Palace was moved – both huge undertaking – and as a result while Greece is represented at one end by the Achilles Monument Rome holds down the other with the Marble Arch and Hyde Park and London are the better for it.

Part of the mythology England likes to produce is an image of a royal coronation at Westminster Abbey followed by a quick trip to the Palace of Westminster to bestow blessings (albeit secular ones)on the houses of Parliament – and to convey that this has been going on since time immemorial. In fact the United States Capitol is older than the current building housing Big Ben and the nanny state. Although there has been a seat of government on the site long before the swamps of Washington were drained the current building dates from its completion in 1870 after the previous one had been destroyed by a fire in 1834. It would have been a must stop for the tourist of 1900 as much for its newness and novelty as for the wigs on whigs and not even its early perpendicular Gothic architecture – impressive though it may be – could give it an ancient air any more than the new St. Paul’s could claim to be a consecrated worship space.

Absolutely unrelated to London Bridge is falling down is the Tower Bridge – which you still have to go to London to visit since the London Bridge in Arizona is the relocated 1831 London Bridge that spanned the River Thames in London until it was dismantled in 1967 – is a combined bascule and suspension bridge in London, over the River Thames close to the Tower of London, from which it takes its name. Started in 1886 and taking eight years to complete the bridge was officially opened on the 30th of June 1894 by The Prince of Wales (later Edward VII), and his wife, Alexandra of Denmark [part of Victoria’s effort to have all European royalty tied to England by marriage].

The bridge is in many ways a marvel of Victorian engineering with the towers supporting the suspension sections and the bascule [draw bridge] section being operated by pressurised water stored in several hydraulic accumulators. With the water stored at 750 psi and the accumulators comprised of 20-inch rams on which sits weights to maintain the desired pressure. Long before the age of diesel or electric the accumulators were driven by two 360 hp stationary steam engines – and the system operated until 1974.

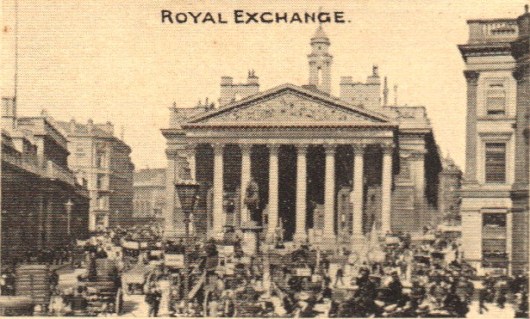

The Royal Exchange was London’s stock market – although brokers had been banned from the original exchange in because of their rude manners – the building pictured here opened in 1845 and housed some of the most polished and accomplished liars of the 19th century. This would have been the spiritual home of Joseph Chamberlain and since the bridge that Macaulay had his painter standing on is now in Arizona we must assume that while Rome remains the great spiritual capital London still has pretensions to being the center of capital. But we have not despaired of London and it is one of the few places that has preserved so much of what the Young family came to visit. As Chesterton said, Then the people went and did what they liked. Let me no longer conceal the painful truth. The people had cheated the prophets of the twentieth century. When the curtain goes up on this story, eighty years after the present date, London is almost exactly like what it is now. Only Rome is more ancient and wiser but London is still worth the trip.